For the last month or two, I’ve been using a third-party keyboard on my phone called Nintype. Until last fall, Apple didn’t allow developers to put keyboards on the App Store, so this is a reasonably new option for iOS users.

When the first keyboards hit the App Store, I tried Fleksy, which bills itself as the World’s Fastest Keyboard, as well as Swype, the most well-known keyboard replacement on Android OS – it boasts 500 million users around the world. I used Fleksy and Swype for about a week each, but went back to the built-in iOS keyboard each time after deciding that neither presented a meaningful upgrade from the iOS one.

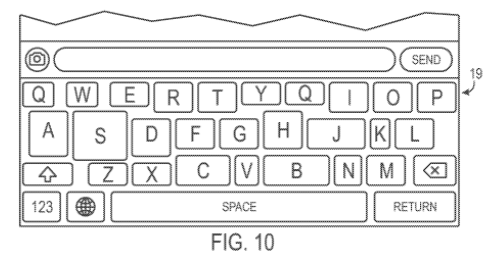

It’s a high bar: the built-in keyboard on an iPhone is pretty great. Since basically forever, it has automatically resized the targets for keys based on what it thinks users are about to type. Example: you type the letter W, and the area where you could tap to type H gets a lot larger than G or N or B or other letters. The phone makes it easier to type H and harder to type all the other letters which would make no sense after a W. These changes are invisible to the user, but this is what it would look like if you could see what the keyboard “thinks” you’re about to type:

This makes the Apple keyboard the most accurate touchscreen keyboard I’ve ever used. I assume Fleksy and Swype both provide some similar feature to improve users’ typing, but it never felt like either keyboard was as accurate as the default iOS one. Less accurate typing means more time correcting your own words, which means less time actually typing. Typing on a phone is slow enough without having to go back every third word and fix it.

Enter the Ninja

Let’s start with the obvious. Nintype is absurd. Just look at it.

Rainbows explode from your fingertips and shoot across your phone’s screen while you’re just trying to text your mother. Responding to an email from your boss looks like a 20th level archmage cast Prismatic Spray on an orcish warband. It just doesn’t look like a keyboard so much as the second act of The Sorcerer’s Apprentice writ small.

But oh, my word. This is absolutely the best keyboard you can get for your phone. I’ve never typed faster or more accurately on a phone before. Period. On a physical keyboard, I usually type at about 80 or 90 words per minute. I average about 70 words per minute with Nintype, which is probably twice as fast as I can type on the iOS keyboard. I dip into the triple digits with Nintype. It’s awesome.

The compromise with writing on a phone is supposed to be (1) yes it’s slow, but (2) I can pull a glass rectangle from my pocket and start writing no matter where I am. The benefits outweight the painfully awkward pecking for someone who types so much faster on a real keyboard. (hashtag eighties kid problems)

But I type just about as quickly on Nintype and a physical keyboard. This is the best compromise ever.

The special sauce

Nintype lets you swipe between letters with both fingers at the same time, and also lets you tap with one finger instead of (or in the middle of) swiping. In theory, this mixture of sliding and tapping is awkward and confusing.

In practice, it’s the input method that makes more sense than either tapping or sliding alone. Before I tried Swype, I assumed that taking a finger and composing a single continuous line through every letter in every word I wanted to type would be arduous and slow me down. That was roughly my experience. I don’t know how to draw the word “experience” with my thumb. I know where to find the letters in the right order.

So now, with Nintype, when my brain can’t decide on the proper route to slide to the next letter, I start sliding my other thumb. Or I just pick my thumb up and tap the next letter. Or I do both. It really is much faster than just tapping each letter out in turn.

As you’d imagine, it’s not immediately intuitive. It took me somewhere between 30 and 60 minutes to get the hang of it. While I was learning, I mostly tapped letters in sequence as usual, and just let my brain find the occasional two letters between which my thumb could slide. During the learning process, typing with Nintype felt about as fast as using the default iOS keyboard to begin with.

Room for improvement

I really, really love this keyboard. I’m shocked at how good it is at being a keyboard.

But, uh, there are some issues.

The first is common to all third-party keyboards on iOS: it’s prone to crashing. Apple did a poor job allowing other keyboards to slot into their OS. Once or twice a day, I’ll have to force quit and restart an app because the keyboard didn’t show up. It’s not a dealbreaker, but it’s hardly ideal. It happens to every keyboard. Even the built-in one.

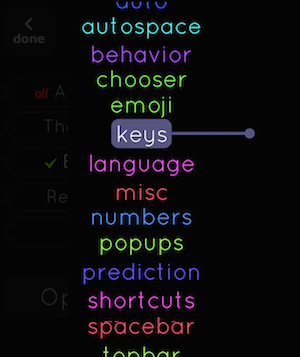

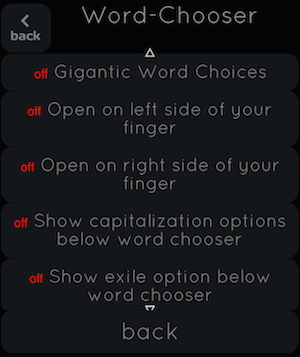

And then there are the options.

An incomplete listing of options screens is on the left, and a sample screen is on the right. Nintype has page after page after page of tweaks, modules, features, and buttons for everything. It’s utterly overwhelming. There are hundreds of boxes to tick and values to adjust. I have no idea what most of them do. Some of them carry grave warnings like “do not disable!” which makes you wonder why there’s even an option there at all. I’m almost surprised Nintype doesn’t come with a text editor and a copy of its own source code for users to edit and recompile, Gentoo-style.

But honestly? The keyboard works perfectly fine without any tinkering. I’ve delved only so deep into the options, even months into using Nintype. There doesn’t seem to be anything to fix, really. I did disable the swooshing wind effects, as well as the “fake LCD distortion” effect. I still have the rainbow-colored lines tracing my every move (to illustrate how Nintype “thinks” my thumbs meant to move). They provide more than enough eye candy on their own: anything more distracting is pointless.

In conclusion

I can’t say enough good things about Nintype. Two-fingered swiping and tapping makes an awful lot of sense in retrospect; far moreso than only doing one or the other. For a product developed and sold by a single guy, it’s astonishing how much he interacts with his customers. Here’s hoping he continues to improve Nintype, and maybe starts removing features instead of adding new ones.